Direct connection or VPN : How Twitter's Geolocation Reveals China's Propaganda Heirarchy?

The Not-So-Model Minority Now Forced to Use VPN software

When I worked at Inner Mongolia Daily, our editor-in-chief Liu Jinghai, was detained by the Chinese Communist Party’s disciplinary inspection authorities.

He had established a real estate service company and appointed his nephew to work there. The nephew, however, withheld salaries from the maintenance staff. In retaliation, one of the unpaid workers killed him. The murderer later walked out of the office building with an axe.

The investigation traced back to Liu Jinghai. When the news spread, some people set off firecrackers in celebration. Liu Jinghai was widely unpopular among Mongolian journalists. For example, when the newspaper received a budget of six million yuan, 5.5 million (773,868 USD) was allocated to the Chinese editorial, while only 500,000 yuan was given to the Mongolian department.

Also our press ID marked us as “Inner Mongolia Daily (Mongolian Edition) / 内蒙古日报社(蒙文版),” . When propaganda officials saw this ethnic label, the alcohol served to us during official banquets would immediately be downgraded. For these reasons, Liu Jinghai never had respect among Mongolian department, largely due to his role in marginalizing us.

But I never expected to meet them again on Twitter.

On November 21, X (formerly Twitter) rolled out a feature that publicly displays user’s geographical information. According to the report,

“The idea is that, by exposing these details, users would be able to make a more informed decision about whether they’re interacting with an authentic account or if the account was a bot or bad actor, looking to sow discord or spread misinformation.”

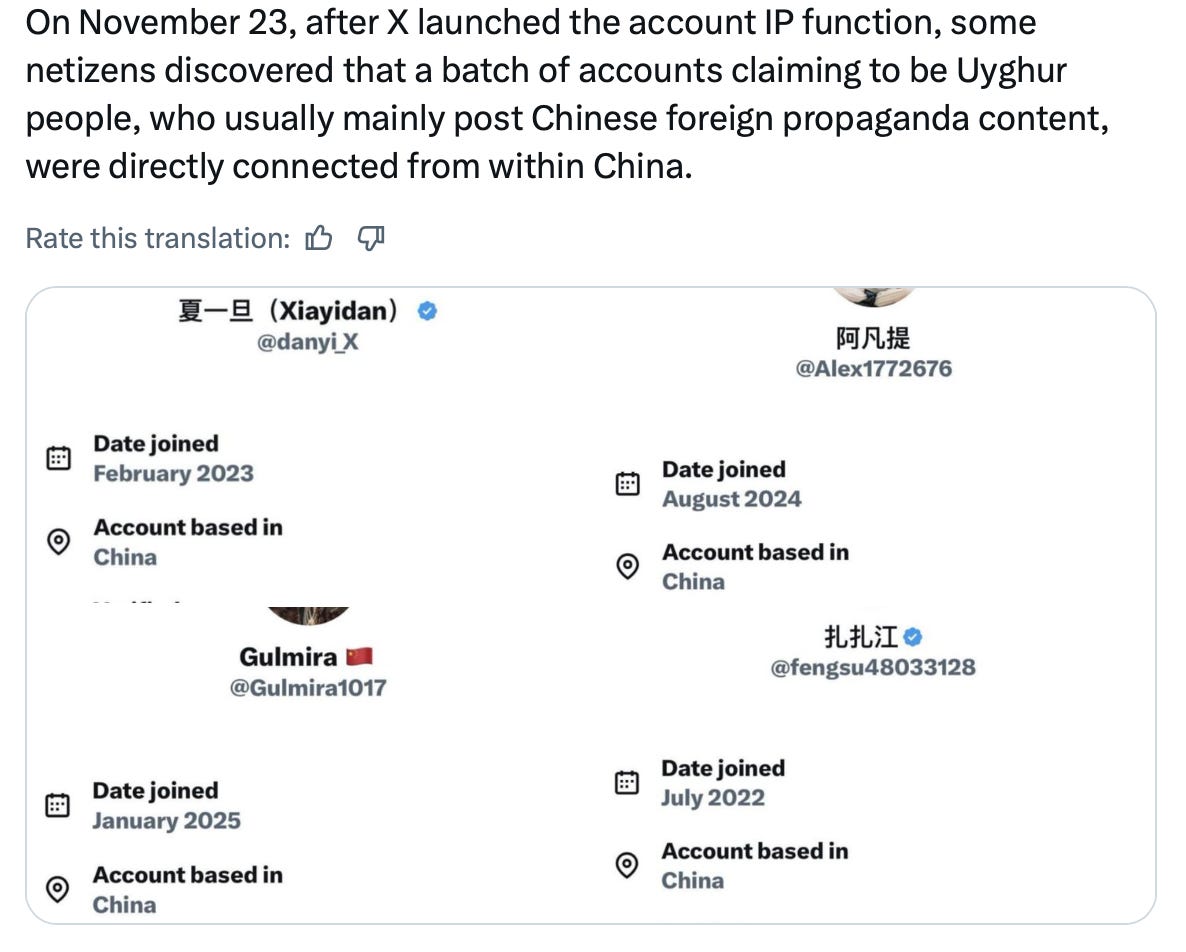

It did more than identifying bots. It also revealed a network of Chinese accounts operating as propaganda machines. Online users found that a number of accounts identifying themselves as Uyghurs are posting pro-Chinese government content, and they were in fact connecting directly from within China.

It was hardly surprising. For many years, Chinese authorities have deployed professional media personnel and state-affiliated institutions to make propaganda campaigns, often disguising themselves as members of specific ethnic groups. These accounts are commonly referred to as Dawaixuan 大外宣 - a term meaning “big external propaganda.”

The idea is to present a version of China that is described by its party-owned media to foreign audiences. Sometimes they are also used to achieve certain propaganda goals.

Needless to say, similar patterns can also be found among accounts claiming to represent Mongolians. A number of Dawaixuan accounts operate under the guise of Mongolian identity online. The following screenshots show some of these accounts.

Here is the link to see 26 screenshots of their accounts.

In fact, the Mongolian diaspora community has long viewed these accounts with suspicion. A Mongolian scholar has further noted that these Chinese state media have begun publishing content in Cyrilllic Mongolian, targeting Mongolian audiences. It was seen as another attempt to influence public opinion in Mongolia itself.

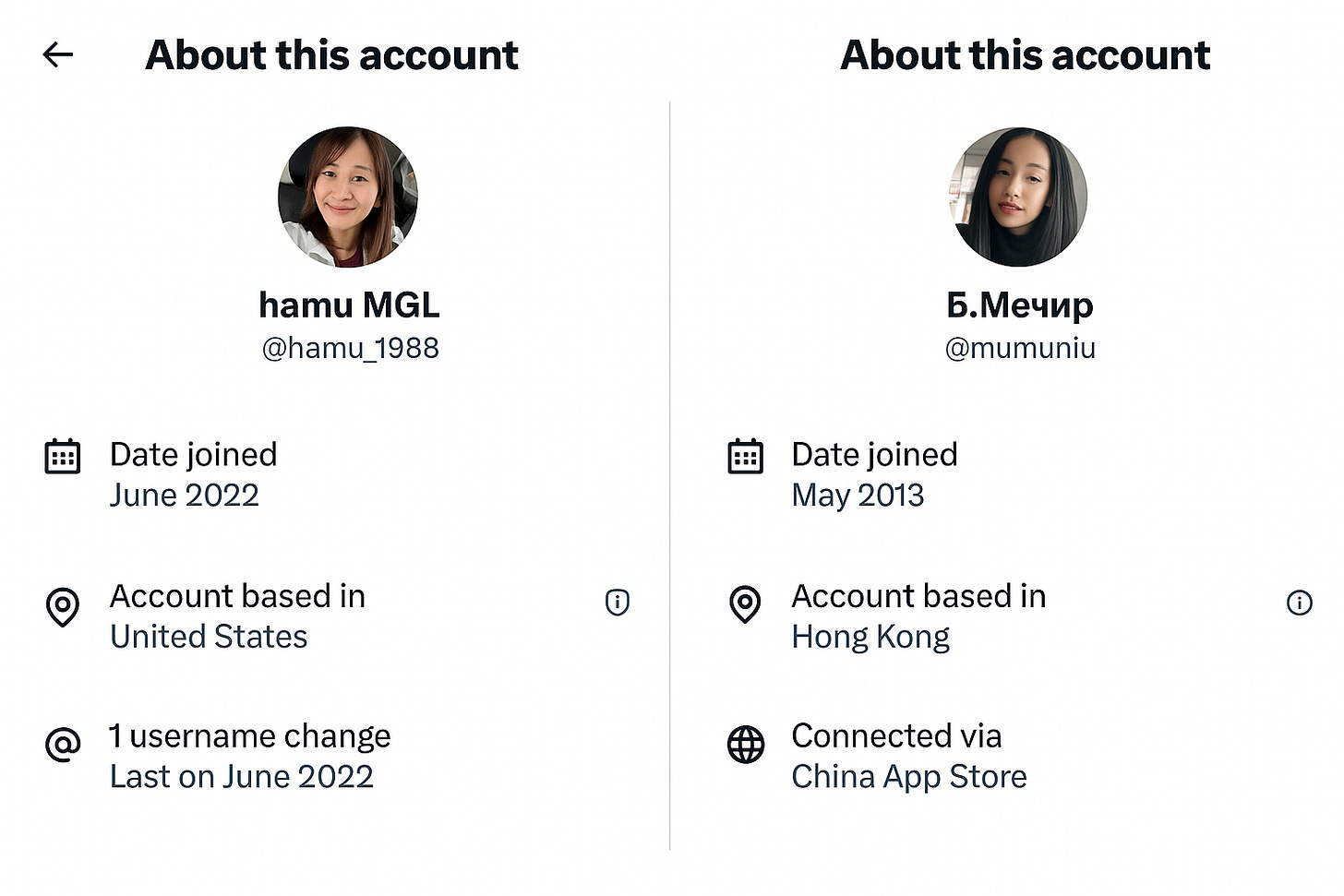

When I examined propaganda accounts associated with Southern Mongolia, I noticed a pattern. Many of these accounts were not connected from China. Instead, their location appeared as Hong Kong or the United States.

On the right side of the displayed location there is a small button. When I clicked, it showed the following explanation:

“One of our partners has indicated that this account may be connecting via a proxy — such as a VPN, which may change the country or region that is displayed on their profile.This data may not be accurate. Some internet providers may use proxies automatically without action by the user.”

Now it is interesting to note that the Dawaixuan accounts from Xinjiang pretending to be Uyghurs are directly connecting from China and those from Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region are operating through VPN softwares.

This raises an interesting question: Why is it different?

In my opinion, there can be two explanations.

First, after the 2020 protests, the word “Mongolian” has been shadowbanned within China’s political discourse. The absence of international media attention, and China’s intentional cover up, the Mongolian issue cannot be fully explained, and cannot be entirely ignored. As for the Uyghurs, the matter must be extensively answered and reported to the international society. It shows how Beijing calculates risk regarding which minority issues are considered globally sensitive.

Second, very awkwardly, many of these Mongolian Dawaixuan accounts on Twitter are operated by people who were once my colleagues. That is also the reason why I wanted to mention Liu Jinghai’s leadership at the start. The current financial conditions simply do not allow them to maintain a high speed direct connection to the international internet. Instead, they are using some kind of VPNs because of the money problem.

Some communities are showcased, and others are quietly managed. The difference between the direct connection and using the VPN is not only showing the technological difference but also the hierarchy rooted deeply in class / political / urgency to showcase.

But the real question remains. The question is, who decides which content and what kind of connection you were supposed to use, if you were a reporter, still trapped inside the system?

(Andy Borjgin also contributed to this article)

The detail about VPN usage versus direct conections revealing not just technical choices but actual hierachy within propaganda operations is fascinating. It makes sense that underfunded operations would use cheaper VPN solutions while high-priority narratives get better infrastructure. This unintentionaly exposes how Beijing prioritizes which minority issues need more sophisticated handling on the global stage.